Know Your Lore TFH: The lost origins of Hallow’s End

What do we know about Hallow’s End?

Not nearly enough. Hallow’s End was introduced in-game as a tie-in to the real world Halloween, an excuse for pumpkins and spooky things — and that’s great. But there is lore to the holiday, and since it’s rolling around again, I felt like it would be a good time to talk about it. More so, though, I would also love to talk about new lore that I feel strongly would contribute well to the holiday in the future. I discussed it already this week, but by necessity I didn’t cover it as deeply as I wanted to.

Well, that’s what KYL is for — so buckle up, we’re about to talk about what we know and what we don’t know about Hallow’s End.

This is a Tinfoil Hat edition of Know Your Lore, meaning that I take what we do know about the lore of the holiday and then I start speculating like mad about what it might mean. Take my conclusions with a whole box of Morton’s please.

Oceans of lost time

Hallow’s End has been celebrated in Lordaeron and Gilneas. In Lordaeron, it went back so far that no one remembered its origins — the people of Lordaeron honored it in a series of festivals, ranging from revelrous to elegiac, leading up to the large celebration on the day of Hallow’s End itself. The holiday combined elements of a harvest festival with those of what we’d call a solstice — a celebration of the bounty of the harvest and the burgeoning life it symbolized, all contrasted with the oncoming winter months and the lean times they brought with them.

There was also a strongly liminal aspect to the holiday. Hallow’s End was about the barriers between life and death wearing thin, a time of year suitable for contemplating what you didn’t want to bring with you into the new year that lay on the other side of winter. Azeroth being what it is, the metaphor of it all — leaving behind those things that haunt you — becomes quite literal and manifest. The actual dead and departed are able to walk the world as freely as the living, and the rites and trappings of the holiday reflect that. The burning of wicker effigies serve as a means to purge oneself of those burdens one doesn’t wish to carry with them into the long cold dark of the winter. It also serves as an actual tool to use when there are literal dead walking, for the pragmatic among us.

Of course, this was before Lordaeron found itself a kingdom of the dead. Becoming Forsaken changed Hallow’s End fundamentally — when once the holiday served as a means to purge oneself of being haunted by the past, the Forsaken of Lordaeron saw it as a means to acknowledge and even celebrate their unique place in the world, neither truly dead nor alive. For the Forsaken, Hallow’s End is theirs — it’s a holiday that puts their unique condition in the center of its purpose. For when you are the lingering dead, the time when the difference between life and death is at its thinnest is clearly of great meaning to you.

The time between times

As a result, the holiday has become two very different things. The Humans of Stormwind, instructed by their recently returned Gilnean allies, use the holiday in its older form. They use it as a time for dealing with regrets and divesting oneself of those thoughts, feelings, memories, and other trappings that hold one back or obsess them before stepping into the future. The Forsaken use it as a celebration of what they’ve become — their undead state makes them essentially the embodiment of all those things that the world wants to leave behind. Their refusal to be ignored or abandoned transforms the holiday into a celebration of their own role as liminal beings. They straddle that same line the holiday does, and in them, the barriers between life and death are thin indeed.

But it would be a mistake to say that either version of the holiday is wrong, or even that either version is the original meaning — because, in truth, we have no idea. We don’t know how old Hallow’s End is — with the chaos in Stromgarde and Arathi, we have no way of determining if the people of Strom celebrated anything like it before the Arathi Empire fractured into the antecedents of today’s Alliance.

Still, there are tantalizing hints. Thoradin was the leader of the original Arathi tribe, and they did not worship the Holy Light or Titan figures such as Tyr. Both of those elements were brought in by Lordain and his followers, who lived in modern Lordaeron in the region where Tyr’s tomb (Tirisfal) now sits. But Lordaeron at its height was a massive kingdom, taking up the area we now know as Tirisfal Glades and the Plaguelands, and many of those people held onto older traditions — Hallow’s End being one of them.

Wicker and fire

Meanwhile, in Gilneas, the traditional “old faith” of the Harvest Witches owed a great deal to an ancient Druid tradition that’s seemingly been lost from the Eastern Kingdoms. Where did this tradition come from? How did they learn it? How did the Harvest Witches manage to keep any of it alive? That, we have not yet seen in-game — but we know there are many sites with ancient Druid connections in the Eastern Kingdoms. There’s the Twilight Grove in Duskwood, Seradane in the Hinterlands, and Tal’doren in Gilneas, where the ancient Druids of the Scythe slept imprisoned in the Emerald Dream. Possibly some of their knowledge of Druidic arts seeped into the dreams of the Gilneans who lived nearby.

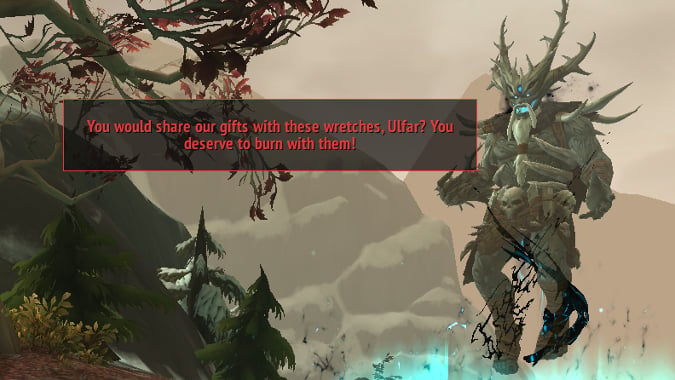

But there’s another people in the region who tapped into dark Druid powers — the Drust of ancient Kul Tiras’ Drustvar region. A barbaric people who bear a very close resemblance both to the Humans who supplanted them and the Vrykul who were ancestral to the Humans. Possibly to the Drust as well — the various beliefs of the Drust Thornspeakers and their Kul Tiran pupils and replacements seem hauntingly familiar when compared to the Hallow’s End rituals. Building a wicker man and burning it to symbolize dealing with the burdens that cross between the lands of the living and the dead? We see this in Drustvar, with an entire cult dedicated to using wicker men in their rites.

Indeed, the fact that the Drust use wicker constructs as an army and that the Order of Embers uses fire against the Drust makes me wonder if, at one time, the Drust ranged across a wider swath of ancient Azeroth than we know. After all, from the time of the first diaspora of Humans before the Curse of Flesh had fully converted their Vrykul forebears to the rise of Strom some 2000 years ago, there’s a stretch of time nearly 10,000 years long. We know very, very little about what Humanity was like during that time. Why did it take so long for a Human society to arise on Azeroth when there were Elves and Trolls warring for dominance? Clearly it wasn’t a lack of ability holding them back.

The ancient door opens

Was Humanity engaged in a generational conflict with a dark offshoot of the Vrykul who used wicker constructs to house the souls of their dead, perhaps in an attempt to circumvent the Curse of Flesh? And did they slowly drive these opposites out of their lands, using fire and the faith of Lordain to slowly push them further and further to the edges of the continent?

It would explain why the Drust were so immediately hostile as soon as the settlers from Gilneas arrived on Kul Tiras — from their perspective, they’d found an island free of their hated enemies and their harvest religion, where they could practice their own form of Druidism that toyed with the edges of death and rebirth — and then even that last refuge was discovered. And what we see of the Drust Thornspeakers and Gorak Tul shows us that Drust Druidism certainly could have inspired a holiday like Hallow’s End. The burning of the wicker men being a distant memory of the war against Drust wicker constructs, while the idea of Hallow’s End as a time where the barriers between life and death are thin certainly has echoes in even the relatively benign Druidic arts of the Thornspeakers.

Perhaps the gateway to Thros gapes open especially widely at the end of autumn and the beginning of winter — it is called the Blighted Land, after all, and winter is often associated with blights. It’s all speculation, but you have to admit it all makes a kind of sense. Hopefully, we’ll find out more about the Drust, their origins, and how they connect up with similar practices from elsewhere on the Eastern Kingdoms — I’d love to see more about them.

Please consider supporting our Patreon!

Join the Discussion

Blizzard Watch is a safe space for all readers. By leaving comments on this site you agree to follow our commenting and community guidelines.

@MatthewWRossi

@MatthewWRossi