Off Topic: The shrink wrapped dinosaur problem

One of my favorite dinosaur/paleontology books is All Yesterdays. It’s been out for six years edging towards seven, and it’s a book with a simple but interesting premise: it renders dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals with a more speculative eye, and then uses modern animal skeletons to show the limitations of most paleo reconstruction art. There are a great many talented artists doing life reconstructions of long extinct animals, using the bones to guide their art and sheath those long dead skeletons in muscle and skin. But the problem is that not everything about a living animal can be judged from its bones.

For example, we all know what a cow looks like. And even if we don’t, we can always go look at a picture of one out in a field somewhere.

Ce n’est pas une vache

That’s a cow, big as life… well at least it’s a picture of one. This is what they look like. You can see their skin color, their flesh and hair, their hide and muscle and fat and even their udders in the back there. It’s a living animal going about its life, eating and excreting and like all living animals displaying a wide assortment of behaviors. Nothing out of the ordinary there. I bring it up because a lot of those things we know about cows come from observation of the living animal, which is not something we can do with dinosaurs or other extinct animals. We’re purely working from fossils — we don’t even have their bones, just fossilized replicas of those bones made by millions of years of geological work.

And this matters because when working from fossils, there’s only so much you can actually learn. More than many understand, in some cases — for example, some fossils preserve the outline of the body’s integument, so some traces of what its skin or flesh looked like are preserved. This is how we know that Archaeopteryx had feathers: they’re preserved in the stone around the fossil itself. But not all fossils are so well preserved. Many are utterly fragmentary, and none of them can preserve entirely soft tissue in a fully intact state. While inferences and theories about behaviors can often be derived from fossils, behaviors themselves do not fossilize.

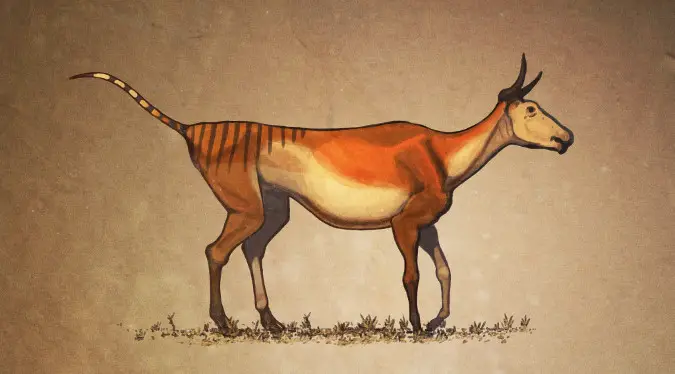

So to go back to our friendly cow above, this is what it would look like if we found a cow skeleton and reconstructed it the way we usually do a dinosaur.

Not just the bones

All Yesterdays points out that there are compelling reasons for this tendency in dinosaur art, especially from artists who are trained to highlight the anatomical features of the animal and not to invent details there’s no evidence for in the bones. That cow reconstruction above is wrong, but we only know it’s wrong because we can go and look at a living cow whenever we want. We don’t have a living T-Rex or Spinosaurus to go compare to our reconstructions of them, and while we know they had digestive systems and reproductive organs (we’ve found enough dinosaur eggs) we don’t really know the details, because those soft tissue structures don’t fossilize.

We are, essentially, left in a world where some of the best dinosaur reconstructions likely look far from accurate. This infamous cross section of an owl makes a related point — without its feathers, owls look more like some kind of buzzard than they actually appear in life, and unless the fossil is astonishingly detailed you simply wouldn’t know that from looking at the bones. The artists aren’t wrong to play it safe in their reconstructions, but that doesn’t change the limits of our understanding. This tendency to depict dinosaurs without fat or feathers, with their skin and muscle so tight against their bones that we can see details of their skulls through their skin is called the shrink-wrapped dinosaur problem, because in its own way it distorts the way the animals looked.

Scroll down to the bottom of this review of All Yesterdays and realize that your cat does not look like that. Why do we assume dinosaur heads showed off every bone, when modern birds don’t?

Nature, not always tooth and claw

Dinosaur art tends towards extremes. People don’t often draw a pack of Deinonychus grooming one another, or an Allosaurus sitting and basking in the sun. But we know from living animals that predators do not spend all their time hunting, and even when they do hunt, not every encounter with another animal is an immediate attack. Lions often go drink from the same watering hole as zebras and never once make a move, because it would be wasted energy, or because they’ve already eaten. Wolves often play with their cubs. Even sharks just swim sometimes. One of the best aspects of All Yesterdays is it depicts dinosaurs as animals just living. Behaviors don’t fossilize, but they still have a place in the art that shows these animals to us as living things, because that’s what they were.

Also, it’s possible to get details wrong. One of my favorite parts of All Yesterdays is when they do a hypothetical reconstruction of a baboon, and in it postulate that the grooves on its teeth mean that it was venomous. After all, many venomous animals today have similar grooves on their teeth. But as we know, baboons do not have envenomed bites — the grooves on their teeth evolved independently and they do not have venom glands. But as we know, glands usually don’t fossilize.

All Yesterdays is an important book because it shows us the limits of our understanding. We learn more and more about these astonishing animals every day, and I would never suggest even for a second that what the bones can and have taught us isn’t remarkable. Fossils have shown us things as varied as possible pigments, the remains of feathers, the presence of gastroliths in their digestive tracts, the similarities in bone structure that led the way to the understanding of how birds are essentially living dinosaurs — and much much more. But in doing these reconstructions it’s necessary to be aware of what they don’t show us: the soft tissues and skin and flesh covering those bones, and the behaviors that simply didn’t leave traces in the skeletons. It’s a book to pick up and pour through, wonder at the alternative possibilities suggested in its pictures of dinosaurs at rest or engaging in behaviors we may never have guessed, and even look in shock at the ways familiar animals could be reimagined if all that was left of them was their bones.

All Yesterdays was created by Darren Naish, C.M. Kosemen, John Conway, and Scott Hartman. If you’re looking to learn more about what dinosaurs might have been like, I recommend it.

Please consider supporting our Patreon!

Join the Discussion

Blizzard Watch is a safe space for all readers. By leaving comments on this site you agree to follow our commenting and community guidelines.

@MatthewWRossi

@MatthewWRossi